Entonces, como aprendí sin profesor, pueden llamarme pintor de la selva. Porque sólo quien ha vivido allá adentro es capaz de descubrir los misterios de la naturaleza a través de nuestros hermanos los indios, dueños de la selva.

Hélio Melo

Espacio

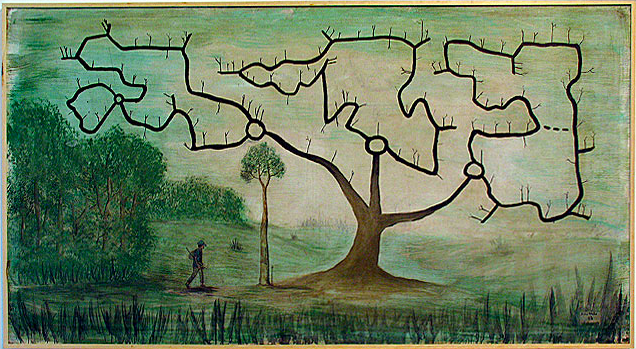

En la obra Estrada de Floresta del artista acreano[1] Hélio Melo (1926-2001) [2] un seringueiro [3] se aproxima a un gran árbol de caucho, que en la selva puede llegar a medir más de treinta metros de altura y casi tres de diámetro[4]. El cuadro no miente, no exagera; no se trata de una licencia pictórica: la realidad es más contundente que la fabulación. En donde el ojo occidental, enfrentado a la selva, solamente ve una impenetrable maraña verde, el cauchero estructura un recorrido, su recorrido: un mapa mental de su diario deambular en busca del sustento. Cuando el seringueiro ve la selva, ve individualmente cada árbol, al que conoce como se conoce a un familiar[5]. En el cuadro de Hélio, cada brazo del árbol representa un camino, un sendero a través de la selva; cada rama, un árbol que debe sangrar; cada nodo circular, un punto de descanso en el trabajo de recolección del látex.

El caucho fue una materia prima esencial para el desarrollo industrial de Europa y los Estados Unidos a partir de la segunda mitad del siglo XIX. Formaba parte integral de la mayoría de las máquinas —válvulas, sellos, correas— y de todos los vehículos. Hay que recordar que para 1927 la fábrica de Ford había producido 15 millones de automóviles Modelo “T”, a un ritmo de casi un millón anual. Algunos observadores han calculado que cada automóvil requería en promedio más de cien libras de caucho en sus diferentes elementos, lo cual nos da una idea de la demanda que llegó a tener el caucho silvestre en el primer cuarto del siglo pasado[6]. Como durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial Japón asumió el control de las áreas tropicales del sureste asiático en donde estaban los grandes cultivos industriales de caucho, el látex americano devino de nuevo un producto estratégico[7], generando un resurgimiento del interés político en las áreas caucheras de la amazonía brasileña. Es por lo menos irónico que el desarrollo de las que en su momento fueron tecnologías de punta estuviera literalmente en manos de personas que, de manera artesanal y gota a gota, le sacaban al “árbol que llora” su preciada sangre[8]. La implacable lógica del capital hizo extensivo este sangrado a toda una comunidad, que sujeta a los vaivenes de la geopolítica, vivió ciclos de desarrollo y crisis a causa de un agente externo que nunca conoció ni pudo controlar.

El árbol de Hélio es, pues, un mapa; pero también es una crónica. Es posible leer en este árbol-recorrido las razones de la tragedia que significó la explotación del caucho en el área de lo que hoy es territorio de Brasil, Bolivia, Perú y Colombia[9]. El problema central de la extracción del látex en América está ligado a una circunstancia biológica; nunca se le pudo cultivar industrialmente de manera eficiente debido a que cuando los árboles están próximos, en filas, se vuelven muy vulnerables a la acción de un hongo mortal[10]. Irónicamente, los ingleses lograron establecer en Malasia grandes plantaciones de árboles de caucho con base en semillas recolectadas en Brasil, que funcionaron debido a que en su nuevo hábitat los árboles carecían de enemigos naturales[11]. Las fallidas experiencias del industrial automotriz Henry Ford en la selva Brasileña en los años veinte[12], y las de los Estados Unidos en Panamá y Costa Rica en los cuarenta evidenciaron que la única forma de explotar el caucho americano era la tradicional, recogiendo el látex de los árboles silvestres. Pero esto significaba una diferencia esencial en términos de eficiencia y rendimiento, lo cual se traducía en una marcada disparidad en el precio de cada kilo producido. Mientras que en los territorios controlados por la corona inglesa un hombre podía sangrar por sí solo más de 400 árboles diarios, produciendo anualmente casi 18 toneladas de látex, un seringueiro brasileño, para producir apenas una quinta parte, debía recorrer cientos de metros a través de la selva de un árbol al otro, desafiando la espesa vegetación, las plagas, los animales y los demás peligros de la selva[13]. Y además, en las épocas más álgidas del boom cauchero en el Amazonas, la presión de lograr un rendimiento absurdo para las condiciones en que se realizaba trabajo, so pena de castigos físicos para él y su familia[14]. Las dificultades derivadas de la extracción, aunadas a las ligadas al transporte del caucho desde las profundidades de la selva hasta los puertos y de allí a sus consumidores finales, significaron un precio significativamente mayor, más de cinco veces el costo de producirlo en plantaciones[15]. Como la lógica capitalista clásica (la industrialización de los procesos) no funcionó debido a la naturaleza misma del árbol, la única forma de que el negocio fuera competitivo era reduciendo el precio en el origen, es decir, en el proceso mismo de explotación. Al no poder optimizar el sistema de recolección —como era la tradición desde la revolución industrial— la única estrategia posible era tener mano de obra barata. El recurso fue volver a la lógica pre-capitalista feudal, es decir, el empleo de trabajadores en condiciones infrahumanas —lo cual rápidamente derivó en la servidumbre más abyecta e inclusive la esclavización, en el caso de los indígenas. A través de un verdadero régimen del terror, los magnates del caucho sometieron primero a los campesinos del Nordeste de Brasil, desplazados por las sequías, mediante un sistema de contrato en el cual todos los transportes, vivienda, insumos y herramientas que recibía cada trabajador tenían que ser pagados con su trabajo, en una espiral de préstamos impagables en la cual a más tiempo trabajado, menores las posibilidades de pagar la deuda.

Cuando ni siquiera esto fue suficiente, comunidades enteras de indígenas fueron obligadas por la fuerza a trabajar en la industria, diezmando por agotamiento y enfermedades a los “dueños de la selva”, cuya tragedia fue el encontrarse en el camino de la empresa civilizadora[16]. El mapa de Hélio muestra las estradas de floresta, que, en palabras de Euclides da Cunha, son “tentáculos de un pulpo desmesurado”, la “imagen monstruosa y expresiva de la sociedad torturada que moraba en aquellos parajes”[17]. La selva como edén impoluto devino infierno: “El seringueiro es sobre todo un solitario, perdido en el desierto de la selva, trabajando para esclavizarse. Cada dia en un seringal corresponde a un trabajo de Sísifo —saliendo, llegando y nuevamente saliendo para las estradas en el medio de la selva, todos los días, siempre, en un ‘eterno giro de encarcelado en una prisión sin muros’[18].

Seringeiro sangrando árbol

Tiempo

Dado que el seringueiro debía seguir una rutina precisa en su trabajo de acopio de la leche vegetal, el árbol de Hélio Melo es también una medida de tiempo: una jornada de trabajo. Cuarenta y tres árboles en el primer recorrido, en el cual hacía las incisiones en el tronco y dejaba colocadas las tigelinas, pequeños vasos en lata en donde goteaba el látex. Cincuenta en el segundo, cuarenta y nueve en el tercero. Más tarde, luego de un breve descanso, volvía sobre sus pasos, recogiendo en baldes el contenido de cada vaso. El final de la jornada lo ocupaba en ahumar el caucho recogido para solidificarlo en grandes balas llamadas pelas.

- Según nos dice el cuadro, en un día el seringueiro de Hélio sangraba casi ciento cincuenta árboles. No sabemos a ciencia cierta qué distancia recorría, pero si de acuerdo a los botánicos los cauchos en su estado silvestre están usualmente separados entre 100 y 150 metros uno de otro, podemos pensar que en un día un trabajador podía caminar casi 50 kilómetros—la distancia para atravesar el Sao Paulo de hoy— entre el sangrado de los árboles y la posterior recogida del producto, bajo el calor inclemente de la selva húmeda[19].

El seringueiro carga un rifle, está armado. Este seringueiro-soldado es Hélio mismo, quien fue “Soldado da Borracha”[20]. Hélio fue uno de los casi 60.000 jóvenes brasileros que participaron en un programa liderado por los Estados Unidos durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial (destinado a contrarrestar los efectos del bloqueo japonés a la producción asiática de caucho), puesto en práctica en la Amazonía con el concurso del Estado Brasileño. La Batalha da Borracha fue una empresa motivada por las necesidades de la industria de la guerra, y por lo tanto una empresa bélica; el seringueiro devino de esta manera un soldado. Su misión: elevar exponencialmente la producción de borracha, de las exiguas 16.000 toneladas logradas en 1941, a 70.000 anuales. Para un incremento tan importante se requerían más de 100.000 trabajadores, razón por la cual se puso en práctica una agresiva campaña de propaganda. A los hambreados habitantes del Nordeste, afectados por una sequía que parecía no tener fin, se les bombardeó con imágenes tendenciosas, carteles que mostraban el látex saliendo a chorros de los árboles para ser recolectado sin esfuerzo en baldes, y que resaltaban el verde del Amazonas como el mítico ElDorado de exhuberancia y riqueza en un Nordeste asolado por la sequía. Sin tener mucho que perder, muchos se enrolaron en el programa. Pero ni siquiera los incentivos económicos fueron suficientemente efectivos para captar el contingente humano necesario para tamaña empresa, razón por la cual se acudió al reclutamiento forzado. Miles de jóvenes Nordestinos acosados por la pobreza decidieron seguir este rumbo, confrontados a la alternativa de pelear en el frente de batalla contra las fuerzas del Eje. Más les hubiera valido: de los 20.000 soldados que pelearon en Europa, murieron apenas 454; en contraste, de los casi 60.000 soldados da borracha enviados a la Amazonía entre 1942 y 1945, casi la mitad sucumbieron a la selva sin haber disparado un tiro[21]. La explotación de los soldados da borracha repitió punto por punto el injusto esquema de trabajo del primer boom cauchero, llamado “sistema de aviamento”, en el cual el trabajador siempre debía más de lo que producía. Como legalmente se le impedía abandonar el seringal sin haber saldado su deuda, el viaje se convertía siempre en un viaje sin retorno, y el contrato en un contrato de esclavización.

La circularidad del recorrido propuesto por la seringueira de Hélio es en consecuencia el tiempo circular: el eterno retorno (de la tragedia)[22].

Energía

El cuadro de Hélio Melo sorprende por su síntesis y por la complejidad de los códigos que maneja. En efecto, a pesar de ser autodidacta en arte, Hélio no debe ser considerado un artista naif. Sus representaciones de la selva —sus usos, sus mitos y sus personajes— no solamente están exentas de inocencia, sino que debido a su profundo conocimiento del territorio físico y social que retrató, su obra está llena de claves ocultas, referencias que solamente quien conoce la selva puede descifrar. Es una representación desde la experiencia directa. Hélio, nacido y criado en un seringal, aprendió por sí mismo a pintar en medio de la selva y tuvo en consecuencia que desarrollar su propio lenguaje pictórico[23]. Como afirmaría Eduardo Galeano refiriéndose a Evo Morales, “el único lenguaje digno de crédito es aquel nacido de la necesidad de decir”[24]. Hélio desarrolló un lenguaje muy particular en el cual los árboles se vuelven vacas y terneros, los burros y las tortugas se suben a las ramas, las Seringueiras devienen caminos, y los Seringalistas, dueños de la tierra, son burros indolentes que observan a los seringueiros trabajar desde la comodidad de sus hamacas.

Entre los varios libros que Hélio publicó con medios precarios[25], uno de ellos —escrito poco antes de morir— se enfoca en la necesidad de salvar la selva, amenazada por la explotación masiva de madera, los monocultivos extensos, las carreteras, y en general los efectos del progreso capitalista impuesto a la realidad de la selva. El caucho fue talado para dejar grandes áreas libres para la ganadería, y al desaparecer el árbol, comunidades enteras quedaron sin posibilidades de subsistencia. “Fue muy triste el destino del caucho, que lamentablemente quedó sin historia. Se saben algunas cosas a través de personas de edad, algunas de esas personas ya no están, pero dejaron testimonios sobre la tumbada y desaparición del caucho. El resultado es que nadie se atrevió a escribir su historia. Por suerte, luego se descubrió la Seringueira, en 1880. De la misma forma que el caucho tuvo un triste fin, los seringueiros tienen una historia dolorosa. La leche de la seringafue y todavía es suplantada por la leche de vaca”[26].

El arte de Hélio no es el arte de un iluminado, en el sentido que se le da a muchas producciones del llamado art brut, sino la expresión visual de un inventario de prácticas en vías de extinción de un personaje con plena conciencia de lo que estaba en juego. Pero sí es un “arte iluminado”. La luz particular de las obras de Hélio Melo, cautivó a muchos, entre ellos al escultor Sergio Camargo[27], quien al respecto escribió: “¿Caso de simbiosis estética con la selva en que vivió? Así se explicaría naturalmente ese fenómeno, sin dar cuenta todavía de su motivación profunda en conocer, por el trabajo del arte, los meandros luminosos que supo percibir; por ejemplo la imanencia compleja de la luz suntuosa, curiosamente definida con la mayor precisión en dibujos de sabia naturalidad. Así la limpia alborada, el lento llegar de la oscuridad nocturna, las travesuras de la luz en las ramas y su paso efímero en la textura rugosa de los troncos; las claridades luminescentes, los suaves abrigos de sombra, los finos recorridos y los amplios espacios que, plenamente, la luz de Hélio Melo ocupa”[28].

Materia

El cuadro de Hélio habla de la selva. O más exactamente la selva habla a través de la obra de Hélio, literalmente. Ante la ausencia de pigmentos para sus obras, Hélio Melo desarrolló su propio método para obtenerlos macerando hojas (presumiblemente del caucho mismo), cortezas, raíces y frutos, y utilizando, según la leyenda local, el látex como aglomerante[29]. Esta es la razón de la coloración verdosa característica de sus obras. Uno de los recursos pictóricos recurrentes en el trabajo de Hélio es la aparición de una fila de hojas afiladas en el margen inferior del cuadro, que establece una especie de primer plano teatral que sitúa la acción en “la selva”. Esta cortinilla de hojas no ha sido pintada: se trata de una huella, pues ha sido lograda con hojas lanceoladas, mojadas en pigmento y aplicadas directamente en el soporte a manera de sello. La pintura de Hélio no solamente representa la vida en la floresta, sino que presenta la selva a través de su uso extensivo como materia y como pincel.

Poéticas (micro)políticas

La Estrada de floresta de Hélio puede también ser leída en el contexto de la recuperación de los valores culturales y las tradiciones de la extracción del caucho en un momento en el que las empresas madereras, los ganaderos y los cultivadores de cereales estaban obteniendo concesiones del estado para talar la selva. Acre es, no hay que olvidarlo, el territorio de Chico Mendes, también seringueiro. Chico combatió la destrucción de la selva con medios no convencionales, como los llamados empates —acciones colectivas de activismo social no exentas de un carácter poético— en los que comunidades enteras de hombres, mujeres, ancianos y niños se tomaban de las manos para rodear a los trabajadores contratados para talar los árboles. Mediante esa estrategia de coerción pacífica, logró defender grandes extensiones de tierra que habían servido de sustento a comunidades enteras, en contra de los intereses de los grandes terratenientes [30]. Chico lideró el concepto de reservas extrativistas, una acción que va más allá de la defensa a ultranza de la selva en la tradición de los ambientalistas. Las reservas extrativistas no consisten solamente en la conservación de un recurso natural —la selva— para contrarrestar una deforestación masiva para la ganadería y el monocultivo, sino la preservación de un uso cultural, realizado por generaciones de indios y colonos a través de los siglos: la extracción del látex. Según el cineasta Adrian Cowell, quien realizó A Década da Destruição, documental sobre los procesos de deforestación en Brasil, “La gran ventaja de la reserva extrativista era justamente su pueblo que podía defender sus fronteras, y que formó una fuerza social que podía actuar en la política local. De la misma forma como ese árbol amazónico que alimenta colonias de hormigas para defenderse contra otras hormigas, los seringueiros y los indios son los defensores natos y naturales de la selva Amazónica [31].

La situación actual de la selva amazónica en los países que la comparten se debate entre una lucha por preservar la naturaleza y los usos sociales y culturales asociados a una explotación milenaria y renovable de los recursos, y la implementación de mejoras —en ocasiones bien intencionadas, pero la mayoría de las veces derivadas simplemente de intereses privados— que facilitarían la entrada de los pueblos “aislados” en la globalización. La insistencia en las vías de penetración como la solución a los problemas de aislamiento de las comunidades amazónicas hace recordar, en su terca insistencia, la construcción de la ferrovía entre los ríos Madeira y Mamoré, gesta íntimamente ligada a la creación de Acre como territorio independiente en 1899 y su posterior anexión por parte de Brasil en 1904 [32].

Ambas tendencias tienen quienes las defienden y detractores furibundos. Los partidarios de los cultivos en extensión argumentan que a mayor producción, mayores los recursos derivados de regalías e impuestos, y más cantidad de puestos de trabajo. Sus contradictores defienden a las comunidades que viven de la explotación racional de los recursos de la selva, aunque la defensa a ultranza de la tradición de la explotación del caucho —elevada a la categoría de mito fundacional— olvida, al idealizarla, que la industria del caucho significó el exterminio de etnias enteras de indígenas: se trató de una prosperidad temporal e ilusoria que sólo benefició a unos pocos, basada en la sangre y el sufrimiento. En muchas ocasiones y a menudo con fines políticos y electorales esta historia trágica es voluntariamente borrada [33] en aras de la conveniencia de un mito fundacional idealizado que pueda dar cohesión y sentido de pertenencia a una comunidad, que puede ser cooptada políticamente [34].

Las buenas intenciones son siempre unilaterales, y no necesariamente compartidas por el destinatario de la dádiva. La imposición de patrones foráneos no encuentra ya un terreno fértil para su afianzamiento, en un contexto políticamente más maduro. El etnobotánico Wade Davis anotaba que al enfrentarnos a comunidades cuya historia, costumbres y mitos desconocemos, “idealizamos un pasado que nunca vivimos y les negamos a quienes lo vivieron que cambien. Tal vez olvidamos la lección más inquietante de la antropología. Como dijo Lévi-Strauss, ‘los pueblos para quienes se inventó el relativismo cultural, lo han rechazado’” [35]. Actualmente en Brasil existen una serie de iniciativas como la Universidade da Floresta encaminadas a lograr soluciones locales que tengan en cuenta el saber de las comunidades y su insumo conceptual en la concepción de estrategias de desarrollo cultural y económicamente sostenibles. Al respecto, vale la pena mirar de nuevo al seringueiro de Hélio, sólo frente a su árbol/selva: “Sólo tenemos una solución: dejar todo atrás y, sin ningún constreñimiento, comenzar una nueva marcha, de manos erguidas, procurando construir sin destruir” [36].

La artista eslovena Marjetica Potrč, quien estuvo en residencia en Acre en 2006 invitada por la 27 Bienalde São Paulo, señala cómo el aislamiento puede ser considerado una ventaja relativa, en el sentido de poder desarrollar respuestas propias e inéditas a problemas que son eminentemente locales, incorporando el saber de indígenas, campesinos y seringueiros en la solución de problemas. Esta estrategia permite entender las micropolíticas locales como un modelo a aplicar —en lugar de soluciones globales que desconocen las especificidades del territorio: “en los últimos quince años, grandes áreas de tierra en Acre han sido entregadas a comunidades, incluyendo a la población indígena, para manejo sostenible. […] La sostenibilidad concierne tanto el medio ambiente como la economía. Quienesmanejan estos territorios ven esta economía de pequeña escala tanto como una herramienta para su propia supervivencia como un nuevo modelo económico crucial para la supervivencia del planeta y de la sociedad en general. ¿Depende el futuro del mundo del balance entre territorios controlados localmente y las fuerzas globalizadoras de compañías multinacionales? Las personas con quien hablé definitivamente piensan que sí. Y deberían saberlo, pues lo que llamamos la última frontera mundial, la selva, ha sido cruzada. Así que, en muchos sentidos, Acre representa la última frontera de la tierra [37].

José Roca.

Río Branco/Bogotá, 2005-2006.

—–

[1] El Acre es un estado brasileño en la selva amazónica. Hasta principios del siglo XX era territorio boliviano, pero fue invadido por caucheros y declarado República independiente de1901 a 1904; ese año fue anexado por Brasil.

[2] Ver la entrevista a Hélio Melo realizada por Cristina Leite en la mini-guía dela 27 Bienal de São Paulo.

[3] Seringueiro: trabajador de la Siringa, caucho. (en inglés: rubber-tapper). En Brasil, al látex se le llama también borracha.

[4] Aparentemente, los árboles que se encuentran en Acre, una variación geográfica del Hevea brasiliensis conocida como “Acre fino”, son los cauchos de mayor tamaño entre todas las especies del Amazonas. Davis, Wade, El río. Exploraciones y descubrimientos en la selva amazónica(Bogotá: Banco dela República/El Áncora Editores), 2001, p.423.

[5] “Para ellos [los seringueros], por supuesto, el término Hevea Brasiliensis no quería decir nada. Distinguían los cauchos por el hábitat y por el color de la corteza, dividiendo en tres tipos la que [el etnobotánico Richard Evans], Schultes consideraba una especie única: la seringueira branca, o caucho blanco, de corteza pardusca, lisa y delgada y látex blanco lechoso, que se da en áreas inundadas durante el período de más lluvia; la seringueira preta, el caucho negro, se encuentra en áreas más bajas, húmedas e inundadas durante la mayor parte del año, y su corteza es gruesa, blanda y purpúrea; y finalmente la seringueira vermelha, el caucho rojo, que es el menos abundante y crece disperso en medio del blanco y del negro, de corteza lisa terracotta y un látex cremoso, casi amarillento”.Davis, pp. 416-417.

[6] Davis, p. 355.

[7] Según Trotsky, hacia 1926 Inglaterra controlaba el 70% de la cosecha de caucho mundial, mientras que Estados Unidos consumía el 70% de esa producción, lo cual generó difíciles roces diplomáticos entre los dos países. Trotsky, León, “Europa y América”, discurso pronunciado por Trotsky en Moscú, 1926.(http://www.marxists.org/espanol/trotsky/ceip/economicos/Europayamerica.htm, consultado el 1 de mayo de 2006).

[8] “Los indios lo llamaban caoutchouc, el árbol que llora, y durante generaciones enteras hicieron cortes en la corteza, dejando que la leche blanca goteara sobre hojas en las que se podía moldear a mano para hacer vasijas y láminas impermeables”. Davis, p. 276.

[9] Al respecto del caso colombiano ver La Vorágine (1924) de José Eustasio Rivera, novela en la cual se expone la problemática de la explotación y miseria humana en la selva.

[10] “En la naturaleza, los cauchos crecen dispersos en la selva, aislamiento que los protege de su mayor enemigo, el hongo Dothidella ulei, que ataca sus raíces y follaje. Esta plaga, que se encuentra sólo en los trópicos americanos, es siempre mortal cuando se concentran los árboles en plantaciones, y fue este accidente biológico el que forjó la estructura de la industria del caucho silvestre”. Davis, p. 280.

[11] Hay una controversia histórica sobre este temprano robo biológico, pues hay quienes argumentan que las semillas salieron legalmente del país en 1876. En todo caso, el efecto fue la crisis de la industria cauchera en el Brasil.

[12] Ford recibió en 1927 un área de 2 ,5 millones de acres, en la cual se fundó Fordlandia, un pueblo de más de mil habitantes dedicado al cultivo industrial del caucho. Ante el fracaso menos de una década más tarde (la mayoría de los 1,4 millones de árboles sucumbieron ante la plaga) se fundaría Belterra, con resultados similares.

[13] “Para 1909 Malaya había sembrado más de cuarenta millones de cauchos, a una distancia de tres metros y en hileras rectas, lo que permitía que un trabajador solo pudiera sangrar cuatrocientos árboles cada día; cada uno producía dieciocho libras [sic] de látex al año, más o menos cinco veces el producido de incluso las más fértiles heveas silvestres del Amazonas”. Davis, pp. 364-65. [Nota: debe decir 18.000libras; el cálculo de Davis se basa en un promedio de alrededor de110 libras diarias en Malaya, cinco veces más que el mejor rendimiento de un seringueiro en Brasil.]

[14] “Al final del día, el mejor siringuero, tras doce horas de trabajo, podía producir veinticinco libras. Para algunos de los magnates del caucho aquello no era suficiente”. Davis, Wade, p. 281.

[15] Davis, p. 365.

[16] Davis, pp.281—285.

[17] Cunha, Euclides da, Um paraíso perdido (Río de Janeiro: ed. José Olympio), 1994, p. 215.

[18] Isabel Cristina Martins Guillen en “Euclides da Cunha para se Pensar Amazônia“ La frase final es de Euclides da Cunha. http://www.comciencia.br/reportagens/amazonia/amaz9.htm. Consultada el 30 de mayo de 2006.

[19] En 1997 Hélio Melo fue invitado a participar en Arte/Cidade III, evento artístico en el cual los artistas intervenían diferentes espacios en São Paulo. Su obra consistió en acumular cientos de zapatos que encontró en las calles de São Paulo, conformando un registro escultórico del recorrido de infinidad de personajes anónimos. http://www.pucsp.br/artecidade/site97_99/ac3/artist/helio_melo.html. Consultado el 3 de mayo de 2006.

[20] “Soy soldado da borracha jubilado. Gano dos salarios. Luché para tener una mejor pensión pero no lo conseguí. Ahora, cuando vendo un cuadro gano un poquito más”. Tomado de la entrevista de Cristina Leite, http://www.ac.gov.br/outraspalavras/outras_8/entrevista.html. Consultado el 2 de febrero de 2006.

[21] http://www2.uol.com.br/historiaviva/conteudo/materia/materia_22.html. Consultado el 30 de mayo de 2006.

[22] “Sólo a partir de la Constitución de 1988, más de 40 años después del fin de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, los soldados de la borracha todavía vivos pasaron a recibir una pensión como reconocimiento por el servicio prestado al país. Una pensión irrisoria, diez veces menor que la pensión recibida por aquellos que fueron a luchar en Italia. Por eso, aún hoy, en diversas ciudades brasileras, el día 1º de mayo los soldados de la borracha se reúnen para continuar la lucha por el reconocimiento de sus derechos.” http://www2.uol.com.br/historiaviva/conteudo/materia/materia_22.html. Consultado el 30 de mayo de 2006.

[23] “El título de mi trabajo es selva amazónica, pues tengo un estilo diferente al de otros pintores. Si usted presta atención, va a reconocer cuando se encuentre un cuadro de Hélio Melo, pues nunca cambié mi estilo”. Ver nota 2.

[24] Eduardo Galeano, “A segunda fundação da Bolívia”, Folha de São Paulo 29/01/2006 — Caderno MUNDO-A24

[25] Hélio publicó varios libros, entre ellos: Legendas (Río Branco: Artes Gráfica São José, 2000); Os Mistérios dos Pássaros (Río Branco: Bobgraf Editora Preview, 1996); A Experiência do Caçador e Os Mistérios da Caça(Río Branco: Bobgraf Editora Preview, 1996).

[26] Melo, Hélio, Como Salvar Nossa Floresta. Do Seringueiro para O Seringueiro (Río Branco: INPECA), 1999. p. 13. Hélio se refiere a una variedad de hevea que fue explotada hasta la extinción, antes del látex que se explotó en el siglo XIX. La final hace referencia a la tala de bosques de caucho para ganadería extensiva.

[27] Camargo vio la obra de Hélio Melo en el cartón de invitación a una exposición de arte popular en el SESC Tijuca en 1980.

[28] http://www.ac.gov.br/imagens/helio.html. Consultado el 15 de mayo de 2006.

[29] Esta es una información que me dieron muchas veces en Río Branco quienes conocieron a Hélio Melo, pero que solamente un análisis químico de sus obras podría corroborar.

[30] Entre 1976 y 1988 más de cuarenta empates salvaron a 1,2 millones de hectáreas. Mendes fue asesinado en 1988 por sicarios contratados por el terrateniente Alves da Silva, quien había intentado infructuosamente comprar la hacienda en donde Chico había trabajado para poder expulsarlo.

[31] Adrian Cowell, en http://www.chicomendes.org/chicomendes195.php

Consultada el 10 de abril de 2006.

[32] “Construido entre 1907 y 1912, el curioso ferrocarril, aislado en el medio de la llanura amazónica, eludía diecinueve grandes raudales en el Mamoré y el Madeira y le daba salida al atlántico a Bolivia. Financiado por los brasileños como compensación por la anexión en 1903 del territorio del Acre boliviano, su construcción cobró seis mil vidas, una por casi cada cuarenta metros de carrilera”. Davis, p.424.

Al respecto, uno de los integrantes de la comisión Moring, nombrada por el gobierno imperial para evaluar esta empresa, afirmaba: “Nos entristece ver tantos y tantos rieles en perfecta pérdida, tanta suma de sacrificios sin resultados”. Citado por Foot Hardman, Francisco, Trem-Fantasma. A ferrovia Madeira-Mamoré e a modernidade na selva (São Paulo: Companhia das letras, 2005), p. 126.

[33] No hay que olvidar que el nombre en inglés del caucho (rubber) se deriva de la observación que hizo científico inglés Joseph Priestley en 1770 de que los pedazos de caucho natural, frotándolos a la superficie del papel, servían para borrar los trazos hechos con lápiz.

[34] Según Eduardo Araujo Carneiro y Egina Carli de Araujo Rodrigues, profesores en Río Branco, “El gran asunto es cuestionar la afirmación de que en Acre hubo un pasado glorioso, patriótico y revolucionario. Necesitamos saber que hay otras ‘lecturas no autorizadas’ sobre el pasado acreano. ¿El patriotismo y el término revolución serían formas de disimular la ganancia que los acreanos tuvieron por los lucros ‘astronómicos’ de la borracha y encubrir los diversos crímenes cometidos por los Acreanos: asesinatos, evasión de impuestos, invasión de tierras extranjeras etc? […] Hubo un proceso de instauración de un sentido único. La versión oficial fue históricamente legitimada e ideológicamente construída por un grupo social con objetivos sociales de dominación. El discurso fundador crea una dependencia entre los ciudadanos y sus heroes actuales, los políticos; transmite la idea de un Estado sin conflictos sociales; forja una unión social en torno de un proyecto político”[34]. Enviado al autor por email.

[35] Refiriéndose a la acción evangelizadora en las selvas ecuatorianas en los años 50. Davis, p.346.

[36] Melo, Op.cit. p. 13.

[37] Ver la entrevista a Marjetica Potrč realizada porLuisa Duarte en la mini-guía dela 27 Bienal de São Paulo.

—

The whole of Acre in a single tree

So, because I learned without a teacher, you can call me a forest painter. Because only those who have lived there are able to discover the mysteries of nature though our Indian brothers, lords of the forest.

Hélio Melo [1]

Space

In the work Estrada da Floresta (Forest Highway) by artist Hélio Melo (1926–2001, from the Brazilian state of Acre) a rubber tapper – in Portuguese, seringueiro [2] –approaches a big rubber tree, which in the wild can measure in excess of thirty meters in height and almost three meters in diameter. [3] The picture does not therefore misrepresent or exaggerate; here it is not a case of “artistic license”: reality is more powerful than the imagination. Where the Western eye, confronted with the forest only sees an impenetrable green tangle of vegetation, the rubber tapper conceives a route, his own route: a mental map of his daily round in search of sustenance. When the rubber tapper sees the forest, he sees every tree individually as if it were a member of a vast family. [4] In Hélio’s picture, every limb of the tree represents a path through the forest; every branch, a tree to bleed; each round knot, a point to rest from the toils of gathering latex.

Rubber became an essential raw material for the industrial development of both Europe and the United States from the second half of the 19th century onward. It formed an integral part of all vehicles and most machinery, such as valves, seals and belts. It must be remembered that, by 1927, Ford had produced 15 million Model T automobiles at the rate of nearly one million per year. Some observers have calculated that each car required more than one hundred pounds of rubber for its various components, all of which gives us an idea of the demand for wild rubber in the first quarter of the past century. [5] During World War II, with Japan controlling the tropical areas of Southeast Asia with their extensive plantations of rubber trees, American latex once again became a strategic product, [6] generating renewed interest in the Brazilian Amazon as a source of rubber cultivation. It is ironic at the very least that the development of what was at the time considered cutting-edge technologies should literally have been in the hands of people who worked by hand and milked the precious “weeping tree” of its precious blood, drop by drop. [7] Capital with its own implacable logic extended this bleeding to the entire community, which, subject to the geopolitical vagaries, experienced cycles of development and crisis all because of an unknown overseas agent which could not be controlled.

Hélio’s tree is, therefore, a map; but it is also a chronicle. It is possible to read into this tree-journey the reasons for the tragedy brought about by the exploitation of rubber in the area which today represents Brazil, Bolivia, Peru and Colombia. [8] The key problem in regard to latex extraction in America is linked to a biological circumstance; it could never be cultivated efficiently on an industrial scale due to the fact that when the trees are planted close together in rows they become susceptible to a fatal fungus. [9] Ironically, the British managed to establish vast plantations of rubber trees in Malaysia from seeds that had been collected in Brazil and which flourished due to the fact that in their new habitat the trees were safe from their natural enemies. [10] The failed experiments by Henry Ford in the Brazilian jungle of the 1920s, [11] and those by the United States in Panama and Costa Rica in the 1940s, showed that the traditional method was the only way in which rubber could be exploited; i.e., by gathering the latex from trees growing in the wild. Yet this demonstrated an essential difference in terms of efficiency and yield, which was to be translated into a marked disparity in the price of every kilo produced. While in the territories controlled by the English crown a man could bleed more than 400 trees per day, thereby producing an annual yield of almost 18 tons of latex, a Brazilian rubber tree, in order to produce a mere fifth of that amount, would require the worker to operate within an area of hundreds of meters across the jungle, going from one tree to another, braving the thick vegetation, parasites, wild animals and other dangers of the jungle. [12] pressure to obtain an absurdly unrealistic yield, considering the conditions in which the work was done and the threat of physical punishment for the worker and his family. [13] The difficulties resulting from extraction, combined with those related to the transport of the rubber from the heart of the jungle to the ports and then on to the end consumers, meant significantly higher costs – more than five times that of producing it on the plantations. [14]

Since classical capitalist reasoning (industrialization of the process) did not work due to the nature of the tree itself, the only way to make the business competitive was to reduce the price at the source, that is, the exploitation process itself. Being unable to optimize extraction methods – as was traditionally done since the industrial revolution – the only possible strategy was to use cheap labor, which meant resorting to precapitalist feudal logic: the employment of workers in subhumanconditions, which was soon to result in the most abject enslavement, including the practice of slavery itself where the indigenous peoples were concerned. This was carried out by means of a veritable reign of terror, firstly with the peasants of Brazil’s Northwest displaced by droughts, falling under the yoke of the magnates, through contracts in which all modes of transport, dwellings, materials and tools were to be paid for by each worker out of his wages. This resulted in a spiral of unpayable loans, which became more difficult to settle the longer they worked. When not even this was enough, entire indigenous communities were forced by the “owners of the jungle” into working for the industry, and were decimated by sickness and exhaustion, their tragedy due to having strayed onto the path of “progress and civilization” embodied by the company. [15]

Hélio’s map shows the estradas de floresta [forest highways], which, in the words of Euclides da Cunha, are like the “tentacles of a giant octopus”, the “monstrous image of a tormented society toiling in those parts”. [16] The jungle like a pristine Eden was turned into a hell: “The rubber tapper is above all a solitary figure, lost in the wilderness of the jungle, working his way into servitude. His day at the rubber tree can be likened to a Sisyphean task – setting off, arriving, and setting off again along the paths that cut through the jungle, day after day, on the eternal treadmill of his wall-less incarceration.” [17]

Time

Given that the rubber tapper had to adhere to a strict routine in his labor, Hélio Melo’s tree is also an instrument which measures time: a working day consisting of a first stint of forty-three trees – making incisions on their trunks and attaching small tin containers called tigelinhas to catch the drops of latex – followed by a second stint of fifty trees and a third of forty-nine. Later, after a short rest, he doubles back, using buckets to empty the contents of each tin container. The end of the working day is taken up with curing the latex in order to make it solid, by shaping it into large balls called pelas.

According to Helio’s canvas, the rubber tapper depicted bled almost 150 trees in a single day. It is not known exactly the extent of the distance covered, but according to botanists, rubber trees in their natural state grow at distances of between 100 and 150 meters from one another. We can therefore conclude that in a day a worker probably walked almost 50 kilometers, i.e., the equivalent of crossing present-day São Paulo, between the bleeding of the trees and the subsequent gathering of the product, under the punishing heat and humidity of the jungle. [18]

The rubber tapper is carrying a rifle; he is armed. This rubber-tapper soldier is Hélio himself, who used to be a “Soldado da Borracha” (Rubber Soldier). [19] Hélio is one of almost 60,000 young Brazilians who took part in a rubber-extraction program in the Amazon during World War II, put into place by the United States with the collaboration of the Brazilian government, in order to counteract the effects of the Japanese blockade of rubber production in Asia. The Batalha da Borracha (Battle for Rubber) was undertaken to supply the needs of the war industry and was, as such, a military undertaking; in a sense the rubber tapper therefore became a soldier; his mission being to raise rubber production exponentially from the meager 16,000 tons achieved in 1941 to 70,000 tons annually. For such an increase more than 100,000 workers were needed, leading to the implementation of an aggressive propaganda campaign. The starved inhabitants of the Brazilian Northeast, affected by what seemed an endless drought, were bombarded by tendentious images in the form of posters that showed latex spurting forth from trees in jets, effortlessly collected in buckets, highlighting the green of the Amazon rain forest as if it were some mythical El Dorado of wealth and exuberance compared with the parched Northeast. With little to lose, many enrolled in the program. However, as the economic incentives proved insufficient to raise the human contingent necessary for an enterprise of these proportions, the organizers resorted to forced recruitment. Thousands of young Northeasterners harassed by poverty decided to follow this route as an alternative to fighting the Axis Powers on the front lines, which, in hindsight, would have been preferable: of the 20,000 Brazilian soldiers who fought in Europe only 454 died, compared to the 60,000 “rubber soldiers” sent to the Amazon between 1942 and 1945, almost half of which lost their lives in the jungle without a shot being fired. [20] The exploitation of the “rubber soldiers” was a carbon-copy replay of the inhuman working conditions of the first rubber boom, which was known as the “sistema de aviamento” [debt-peonage system], in which the worker always owed more than he produced. Since he was legally prevented from abandoning the rubber tree without having repaid his debt, the journey was usually only one way, and the contract, a contract of slavery.

The circularity of the journey proposed by Hélio’s rubber tree is the result of circular time: the eternal return (of the tragedy). [21]

Energy

Hélio Melo’s painting is surprising for its synthesis and the complexity of its codes. In fact, despite being self-taught in art, Hélio should not be considered a naïve artist. His depictions of the jungle – its customs, myths and characters – are devoid of innocence, and due to the artist’s intimate familiarity with the physical and social environment portrayed, they are replete with hidden clues and references which only those who know the forest are able to decipher. His depiction is based on direct experience. Hélio, born and raised on a rubber estate, taught himself to paint in the middle of the jungle and was therefore obliged to develop his own pictorial language. [22] As Eduardo Galeano, when referring to Evo Morales affirmed, “The only language which is to be believed is that which is born from the need to be spoken”. [23] Hélio developed a very particular language in which trees became cows and calves, where donkeys and tortoises climb trees, where rubber trees become paths and where the seringalistas – the masters of the rubber estates – are indolent mules observing the rubber tappers at work, from the comfort of their hammocks.

Among the various books that Hélio published with his limited resources, [24] one, written shortly before his death, focuses on the need to save the forest, threatened by massive exploitation of timber, extensive monoculture farming, highways and the overall consequences of progress in the capitalist sense, imposed upon the reality of the forest. Rubber trees are felled in order to clear the land for cattle farming, and with the disappearance of the tree, entire communities are left without any means of subsistence. “The fate of the rubber tree was a sad one indeed in that it remains undocumented. A little knowledge has been passed down by elderly people. Some of those who have passed away have left behind them testimonies to the felling and the disappearance of the rubber tree. The result is that no one has undertaken to write its history. It was fortunate that the rubber tree was discovered in 1880. In the same way that the rubber tree came to a sad ending, the rubber tappers had a painful history. The milk of the rubber tree has been, and is still being, exchanged for the milk of the cow”. [25]

Hélio’s art is not that of one who is enlightened, as many productions of so-called art brut are commonly characterized. It is rather the visual expression of an inventory of nearly extinct practices by one who is fully aware of what is at stake. It nevertheless remains an art which is “illuminated”. The special light inherent in the works of Hélio Melo has captivated many, such as the sculptor Sergio Camargo, [26] who wrote in this regard: “A case of aesthetic symbiosis with the jungle in which he lived? This is of course how one would explain this phenomenon without however taking into account his compulsion to come to grips through his art, with the meandering streams of light which he managed to capture in his art, an example of which was the complex immanence of sumptuous light; strangely enough, defined with greater precision in drawings of wise naturality. The pellucid dawn, the stealth of nightfall, the play of light in the branches and its ephemeral contact with the roughness of the tree trunks; the luminous glades, the gently shaded bowers, the faintly discernible paths and wide open spaces filled with the light of Hélio Melo’s brush.” [27]

Popular art as an expression of traditional culture is based on a combination of elements: a craft passed on from generation to generation, a need for self-expression and a means of sustenance. In contemporary art, reference is seldom made to the aforementioned factors. Popular art and the art of “outsiders” – here referred to as contributions which generally possess a strong voice and a sense of urgency, either stand in contrast to current artistic output or complement it. In the context of the 27th Bienal de São Paulo, the work of Hélio Melo will articulate with other works dealing with notions of territory, boundaries, environmental justice, fair trade, etc., some of which were done in Acre itself: the parody of scientific knowledge in the herbarium of artificial plants by Alberto Baraya, who built a big rubber tree out of latex; [28] the sketch/report by Susan Turcot, which is a reflection on deforestation and its implications for symbolic and mythical readings of the forests and for local inhabitants; the analysis of survival structures and new types of community in Acre depicted by Marjetica Potrč ; the setting up of a system guaranteeing the sustainability of agricultural communities in the forest conducted by the Danish group Superflex, among others.

Subject matter

Hélio’s painting speaks of the jungle, or more exactly, the jungle speaks through Hélio’s works, literally. Faced with the absence of pigments for his works, Hélio Melo developed his own method for obtaining them by crushing leaves (presumably those of the rubber trees themselves) and from bark, roots, fruits and by using, according to local legend, the latex as a thickener. [29] The greenish coloration characteristic of his works is probably a result of this process. One of the pictorial techniques which recur in Hélio’s works is the appearance of a row of tapered leaves in the lower margin of the painting, which establishes a kind of theatrical foreground situating the action within “the forest”. This little curtain of leaves has not been painted: it serves as an indexical trace, since it has been achieved using spear-shaped leaves, dipped in pigment and applied directly to the medium as a kind of stamp. Hélio’s painting does not only represent life in the forest but presents the forest through its extended use as both subject and paintbrush.

Poetic (micro)politics

Hélio’s Estrada da Floresta can also be read in the context of a restoration of cultural values and traditions related to rubber tapping at a time when logging companies, cattle ranchers and cereal farmers were obtaining state concessions to cut down the forest. It should not be forgotten that Acre is the birthplace of Chico Mendes, another rubber tapper. Chico fought the destruction of the forest with nonconventional means, such as what came to be known as empates – collective activism, not without poetic flourish – in which whole communities of men, women, the elderly and children joined hands surrounding the workers who’d been hired to cut down the trees. By means of this strategy, he was able to defend, against the interests of landowners, large stretches of land that entire communities depended on for their sustenance. [30] Chico championed the concept of reservas extrativistas (extractivist reserves), an activity which went beyond the traditional environmentalist “defense to the death” of the forest. The reservas extrativistas were committed not only to the conservation of the forest as a natural resource to counteract the massive-scale deforestation for cattle raising and monoculture, but also to the preservation of a centuries-long cultural heritage, practiced by generations of Indians and settlers: rubber tapping. According to film director Adrian Cowell, known for his documentary The Decade of Destruction on the processes of deforestation in Brazil, “The great advantage of the reserva extrativista was its people who were able to defend its borders and who formed a social movement which might have a say in local politics. In the same way as the type of Amazon tree which feeds colonies of ants in order to protect itself against other ant species, the rubber tappers and Indians are innate defenders of the Amazon rain forest.” [31]

Countries which share the rain forest have entered into a debate to decide between a struggle to preserve, on the one hand, the natural environment and the habits and social customs associated with its long-term sustainable use, and, on the other, the improvement of living conditions, well-intentioned, but most of the time simply serving private interests, which would facilitate access of “isolated communities” to the globalized world. The insistence upon methods of penetration as a solution to the problems of isolation of rain forest communities calls to mind, by its obstinate persistence, the construction of the railway between the Madeira and Mamoré rivers, an event closely related to the creation of Acre as an independent territory in 1899 and its subsequent annexation to Brazil in 1904. [32]

Perhaps the most striking similarity in these two trends lies in their frenzied defenders and detractors. The partisans of extensive farming argue that increased production means more tax revenue, benefits and jobs. Their rivals argue in defense of the communities which live by rational, sustainable use of the forest’s resources, although the defenders to the death of the tradition of rubber tapping – which has been raised to the level of a foundational myth – forget, in the midst of such idealization, that the rubber industry meant the extermination of entire groups of indigenous peoples: in reality prosperity was ephemeral and illusory and benefited only a few, not to mention its legacy of blood and suffering. This tragic tale is conveniently “rubbed out” (erased) [33] in favor of the convenience of an idealized founding myth lending cohesion and a sense of belonging to a community, which might then be co-opted into the political arena. Several local thinkers see the exaltation attending the circumstances of Acre’s transition from territory to state differently. According to Eduardo Araujo Carneiro and Egina Carli de Araujo Rodrigues, “The great question is to unveil the assertion that Acre possessed a glorious past in a revolutionary and patriotic sense. It is important to know that there are other, ‘unofficial’, readings regarding the question of Acre’s past. Might not the patriotism and the term revolution have been ways of hiding the greed harbored by the inhabitants for astronomic profits from rubber as well as the crimes committed by the inhabitants: murders, tax evasion, the seizure of foreign-owned land etc? […] There was a process of instilling a single meaning. The official version was historically legitimated and ideologically constructed by a particular social group whose purpose was to impose their control. The founding discourse created dependence between citizens and their present heroes, the politicians; transmitting the idea of a state without social conflict; forging a social unity around a political project.” [34]

Good intentions are always one-sided, and not necessarily shared by the beneficiary. The imposition of foreign standards could no longer find fertile terrain in which to take root, given a more mature political context. The ethnobotanist Wade Davis noted that by coming into contact with communities whose history, customs and myths we are unacquainted with, we tend to “idealize a past that we did not personally experience, and one which we do not allow those who did, to alter. Perhaps we forget anthropology’s most disquieting lesson. As Levi-Strauss stated, ‘the people for whom cultural relativism was invented have rejected it’”. [35] At present in Brazil there exist a series of initiatives like the Universidade da Floresta [Forest University] geared towards finding local solutions which might take into consideration the knowledge of communities and their conceptual input in the conception of economically sustainable strategies for cultural development, all of which brings us back to casting an eye at Hélio’s rubber tapper, alone and facing his tree/jungle: “There is just one solution: leave everything behind and, without hindrance, blaze a new trail, with hands raised, in an attempt to build and not to destroy”. [36] Marjetica Potrč , who lived in Acre in 2006 points out how isolation can be considered a relative advantage, in the sense of being able to develop local and original solutions to problems which themselves are essentially local, incorporating the knowledge of the inhabitants, small farmers and rubber tappers in solving these problems. This strategy provides insight into the local micropolitics as to which model should be applied, as opposed to global solutions which ignore the specific details of the territory:

In the last fifteen years, large tracts of land in Acre have been handed over to communities, including the indigenous population, for sustainable management. […] Sustainability is as much a concern to the environment as it is to the economy. Those who work these territories see this small-scale economy as both a tool for their own survival as well as a new economic model essential for the survival of the planet and for society as a whole. Does the world’s future depend on the balance between territories controlled locally and the forces of globalization of multinational companies? The people who I have spoken to definitely think that this is the case and it is as well they should, for what has been called the world’s last frontier – the forest – has been entered. In many senses, Acre represents the earth’s last frontier. [37]

—–

Notes:

- See the interview with Hélio Melo conducted by Cristina Leite in the Guide of the 27th Bienal de São Paulo, p. 94.

- Seringueiro: from the word siringa or rubber tree, with the -eiro suffix of an agent.

- Apparently, the trees found in Acre, a variety known as Hevea brasiliensis also known as Acre fino, are the largest of their kind in the Amazon. Cf. Wade Davis, El río. Exploraciones y descubrimientos en la selva amazónica, Bogotá, Banco de la República/El Áncora Editores, 2001, p. 423.

- “For them [the rubber tappers], the term Hevea Brasiliensis held no meaning. The rubber trees were recognizable by the color of their bark. Richard Evans Schultes considered them to be of one variety, whereas the ethnobiologist Richard Evans considered there to be three subdivisions of the same species: the seringueira branca [white rubber tree] with grayish bark, smooth and slender, producing a milky latex, which is secreted in flooded areas during the rainy season; the seringueira preta [black rubber tree], found in the lower areas, damp and flooded for most of the year with a soft mauve bark; and finally the seringueira vermelha [red rubber tree], which is the least abundant and is to be found interspersed with the white and black varieties, its bark a smooth terra cotta and its latex creamy, almost yellow”. Wade Davis, op. cit., p. 416–417.

- Wade Davis, op. cit., p. 355.

- According to Trotsky, towards 1926 England controlled 70% of world rubber harvests, while the United States consumed 70% of this production, which led to diplomatic tensions between the two countries. Cf. León Trotsky, “Europa y América”, 1926. marxists.org, consulted May 1, 2006.

- “Indians called it caoutchouc, the tree that wept, and for entire generations they would make incisions in the bark, allowing the white milky substance drip onto the leaves, molding them by hand into recipients and waterproof sheets”. Wade Davis, op. cit., p. 276.

- In Colombia’s case, see La vorágine (1924) by José Eustasio Rivera, a novel which exposes the problems and human misery engendered by the exploitation of rubber in the forests.

- “In nature, rubber trees are dispersed in the forest, an isolation which protects them from their main enemy the Dothidella ulei fungus, which attacks their roots and foliage. This scourge, which is found only in the American tropics, is always fatal when trees are crowded together into plantations, and it was this biological accident that led to the structuring of the wild rubber industry”. Wade Davis, op. cit., p. 280.

- There is a historical controversy regarding the early biological theft, since there are those who argue that the seeds left the country legally in 1876. In any case, this led to a crisis in the Brazilian rubber industry.

- In 1927, Ford received an area covering 2.5 million acres, in which he founded a village of more than one thousand inhabitants whose main activity was the cultivation of rubber. Due to its failure more than a decade later (most of the 1.4 million trees succumbed to the blight) Belterra was founded, with similar results.

- “By 1909 Malaysia had planted more than forty million rubber trees, at a distance of three meters, in straight rows, which meant that each worker could bleed four hundred trees per day; each one produced 18 pounds [sic]* of latex per year, more or less five times that produced by even the most fertile Amazonian species”. Wade Davis, op. cit., p. 364–65.

* It must be 18,000 pounds; Davis’s estimates are based in an average of 110 pounds a day in Malaysia, five times more than the best output of a seringueiro in Brazil. - “At the end of the day, the best rubber worker, after twelve hours of solid work, was able to produce 25 pounds. For some of the rubber barons that was considered insufficient”. Wade Davis, op. cit., p. 281.

- Wade Davis, op. cit., p. 365.

- Wade Davis, op. cit., p. 281–285.

- Euclides da Cunha, Um paraíso perdido, Rio de Janeiro, Ed. José Olympio, 1994, p. 215.

- Isabel Cristina Martins Guillen IN: “Euclides da Cunha para se Pensar Amazônia”, the last sentence is from Euclides da Cunha, Amazônia, consulted on May 30, 2006.

- In 1997, Hélio Melo was invited to take part in an event representing different artistic spaces in São Paulo. His work consisted of collecting hundreds of shoes which he found in the streets of São Paulo, a “sculpted record” of the journey of all the city’s anonymous inhabitants. Arte/Cidade III, consulted on May 3, 2006.

- “I am the retired rubber soldier. I draw two salaries. I have fought for a better wage, but fought in vain. Now, when I sell a painting I earn a little extra”. Taken from an interview

with Cristina Leite, consulted on February 2, 2006. - História Viva, consulted on May 30, 2006.

- “Only as a result of the 1988 constitution, more than 40 years after the World War II, did those surviving “rubber soldiers” receive a pension as recognition of service to their country. A derisory pension, ten times less that that received by those who had gone to fight in Italy. Consequently, even today, in several Brazilian cities, on the First of May, the “rubber soldiers” gather to continue the struggle for recognition of their rights.” História Viva, consulted on May 30, 2006.

- “The title of my work is the Amazon forest, which is where my style differs from that of other painters. If you pay close attention, you will see where to place the painting of Hélio Melo, since my style has never changed”. See note 1.

- Eduardo Galeano, “A segunda fundação da Bolívia”, Folha de São Paulo, supplement Mundo, p. A24, January 29, 2006.

- Hélio published several books, among them: Legendas, Rio Branco, Artes Gráfica São José, 2000; Os mistérios dos pássaros, Rio Branco, Bobgraf Editora Preview, 1996; A experiência do caçador e os mistérios da caça, Rio Branco, Bobgraf Editora Preview, 1996.

- Hélio Melo, Como salvar nossa floresta. Do seringueiro para o seringeiro, Rio Branco, INPECA, 1999, p. 13.

- Camargo saw Hélio Melo’s work on the invitation card to an exhibition of popular art held at SESC Tijuca in 1980.

- Hélio Melo, consulted on May 15, 2006.

- Baraya’s tree is the exact copy of an enormous rubber tree in Rio Branco and was made from the latex of 2,800 trees like it; like that of Hélio’s, it is also a tree in which all trees are contained. See the image.

- This was told to me on several occasions in Rio Branco by those who were acquainted with Hélio Melo, an assertion, however, that without chemical analysis would be impossible to corroborate.

- Between 1976 and 1988 more than forty empates saved 1.2 million hectares. Mendes was murdered in 1988 by hired killers contracted by a landowner, Alves da Silva, who had vainly tried to buy the farm where Chico had worked in order to have him expelled.

- Adrian Cowell at Chico Mendes, consulted on April 10, 2006.

- “Built between 1907 and 1912, this odd railway, isolated in the middle of the Amazon plains, stretching from the Atlantic to Bolivia, escaped the flooding of the Madeira and Mamoré nineteen times. Financed by the Brazilians by way of compensation for the annexation in 1903 of the territory belonging to the Bolivian Acre, its construction cost more than six thousand lives, approximately one per forty meters of track”. Wade Davis, op. cit., p. 424. In reference to this, one of the members of the Moring Commission, appointed by the Imperial Government to assess the cost of the project, stated: “It saddens us to see so much money squandered at such great sacrifice with so little to show for it”. Quoted by Francisco Foot Hardman, Trem-Fantasma. A ferrovia Madeira-Mamoré e a modernidade na selva, São Paulo, Companhia das letras, 2005, p. 126.

- It shouldn’t be forgotten that the English term “rubber” is derived from the observation made by Joseph Priestly in 1770 that, when rubbed on a sheet of paper, pieces of raw rubber erased the lines of a pencil. Encarta: Caucho.

- Egina Carli de Araújo Rodrigues Carneiro and Eduardo de Araújo Carneiro, “Acre e o mito fundador”, text sent to the author by email.

- Referring to the evangelistic activity in the equatorial rain forests in the 1950s. Wade Davis, op. cit., p. 346.

- Hélio Melo, op. cit., p. 13.

- See the interview with Marjetica Potrč conducted by Luisa Duarte in the Guide of the 27th Bienal de São Paulo, p. 166.